Weaponizing Race

Corruption, Contradiction, and the Illusion of Progress in Modern Black Movements

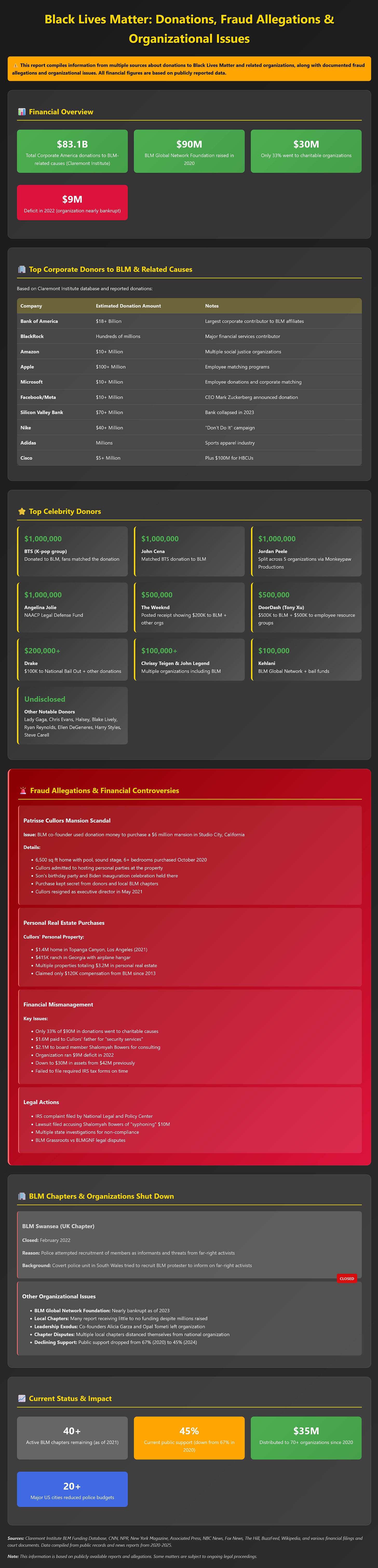

In America, race is currency, weapon, and mask. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the rise of what some call “faux Black feminism” and the public spectacle of the Black Lives Matter movement—a space where slogans of solidarity often hide a scramble for status, profit, and control. The last decade has seen Black celebrities and activists amass unprecedented wealth and cultural influence, while large swaths of the Black community remain trapped in cycles of poverty, surveillance, and state violence.

This isn’t just a story about inequality—it’s a story about contradiction. The same movements that claim to speak for the most marginalized sometimes serve as launchpads for the privileged few. Calls for justice are too often weaponized as tools for censorship or self-enrichment, with the language of revolution masking everything from charity fraud to outright terrorism. Underneath the hashtags and headlines, old hierarchies persist, reshaped by new ideologies: communism repackaged as social justice, solidarity that fractures when power is at stake.

The point of this essay isn’t to dismiss the real harms of racism or the need for change. It’s to ask uncomfortable questions about who benefits from the current order—and who is left behind. To map the uneasy ties between Black privilege and Black poverty, to expose hypocrisy wherever it festers, and to trace how the politics of “liberation” sometimes shade into something darker: coercion, corruption, and the exploitation of suffering for personal gain.

The Curry Family: Basketball Royalty, Modern Feudalism, and Influence’s Shadow

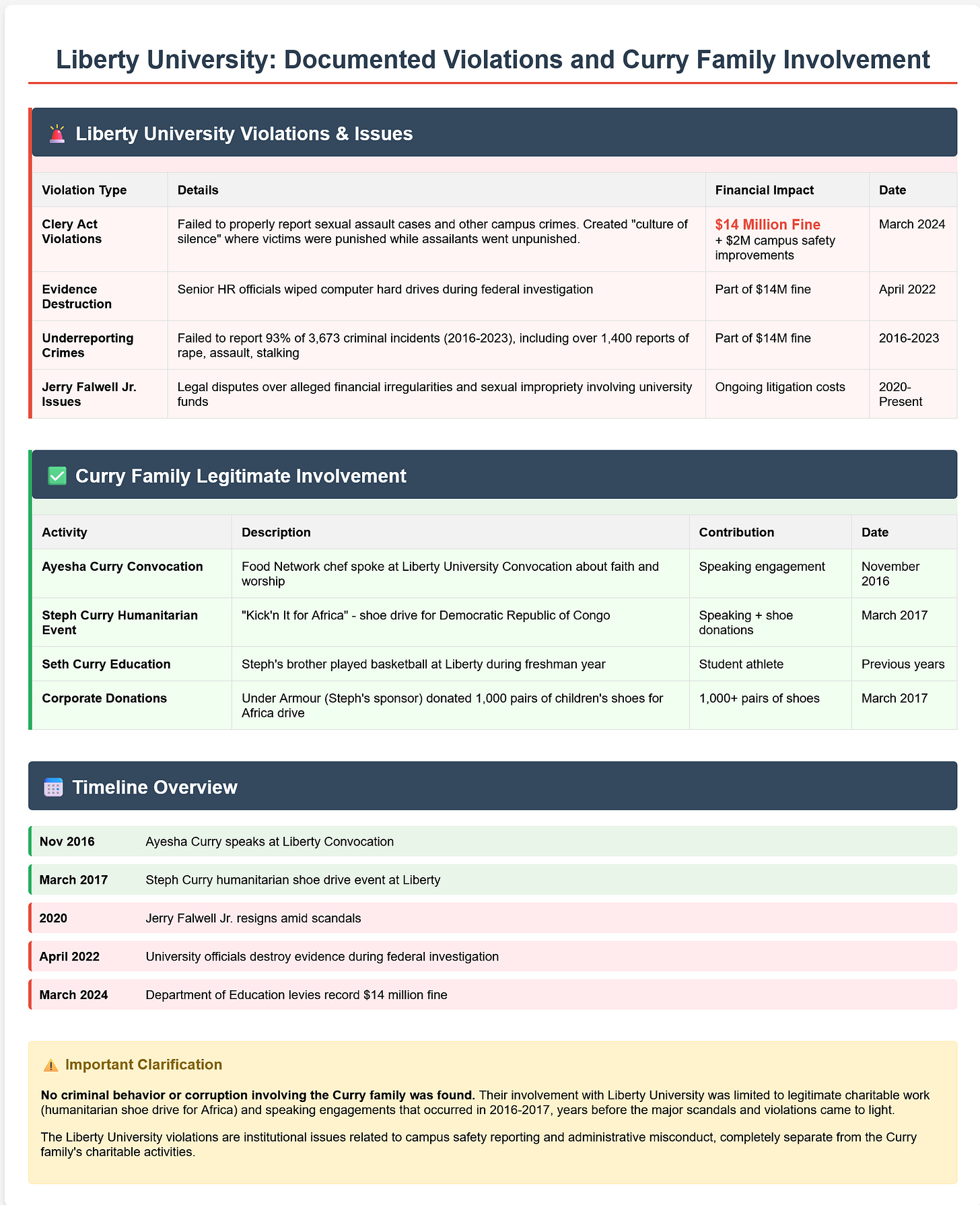

The Curry name has become shorthand for basketball royalty. On the surface, the family’s rise is a feel-good story: hard work, generational talent, and a squeaky-clean image. But dig below the highlight reels and you’ll find something uglier — a tangled web where basketball stardom feeds off-and-on-court power, and influence becomes less about inspiration and more about building dynasties, rolling up opportunities, and leveraging sport for unchecked wealth.

Steph Curry is now more than just an athlete; he’s a global brand, a pitchman, and, increasingly, a kingmaker in business and culture. The numbers alone are staggering. According to Bleacher Report, Curry earned $35 million just to promote FTX, the now-infamous crypto exchange whose collapse vaporized billions in ordinary people’s savings. These endorsement deals aren’t just about cashing in — they’re about buying and selling trust, using fame to turn followers into marks. When the face of the NBA can be bought for a quick payday, what does that say about the system?

It’s not just about endorsements. There’s the relentless roll-up of influence: Curry’s "Underrated" golf tour, his wide-ranging partnerships with brands like Infiniti, and a growing presence in global sports and entertainment. Even the celebrity golf circuit is part of the Curry ecosystem, reinforcing a new kind of celebrity feudalism where access, privilege, and upward mobility are controlled by a handful of basketball aristocrats. The old-school American dream — that sports could be a path out of poverty — now feels more like a lottery, with the winners grabbing everything and the rest left with scraps.

How We Fail Our Young Men

Start writing today. Use the button below to create a Substack of your own

Too good to pass up. Caste incarnate - rebranded.

The risk isn’t just economic. It’s spiritual and emotional. The game that was supposed to unite and uplift now divides: fans idolize stars while feeling more alienated than ever, as the gap between basketball royalty and everyone else grows wider. This is the heart of modern feudalism. The Curry family’s reach extends through business, philanthropy, and international schemes — from Africa’s Basketball League (with its own entanglements in global power games) to high-profile events in places like Qatar and the UAE, where money is often dirty and political agendas lurk just below the surface. Reports by organizations like FATF and The Guardian highlight how easily wealth and influence can be used to launder reputations — and how celebrity athletes, knowingly or not, are often part of these schemes.

Basketball is supposed to be meritocratic, but the Curry family’s story points in the opposite direction. It’s about consolidating power, cashing in on celebrity, and building dynasties that look a lot more like the old feudal lords than the grassroots heroes the NBA likes to celebrate. The influence of the Currys — and athletes like them — has become a double-edged sword. They can inspire millions, but they can also serve as the gatekeepers of opportunity, using fame as a tool to perpetuate privilege and extract wealth from the game itself. Essentially Sports even notes that this level of consolidation could threaten the NBA’s own structure, echoing the power grabs seen in other sports like golf.

In the end, the Curry family’s legacy may not be about basketball at all. It may be about how celebrity, money, and unchecked influence have turned the love of the game into yet another rigged system — one that leaves everyone else spiritually, emotionally, and financially poorer.

Branding Blackness: Slavery, Class, and the Comfortable Distance of Power

In the U.S., conversations about Black identity often get blurry on purpose. You’ll hear “African American” tossed around to describe NBA players, first-generation Nigerian immigrants, and descendants of enslaved people from the Deep South—all in the same breath. Caribbean Americans, too, get folded into this big, vague idea of “Blackness,” as if everyone’s history and culture are interchangeable. What’s lost is the difference: not all Black people in America share the same roots or relationship to this country, and not all are equally shaped by the legacy of slavery. But in the marketplace—especially where wealth and influence are concerned—those differences get flattened. This conflation isn’t an accident. It’s profitable.

Consider the rise of Black billionaires and superstar athletes, especially those who’ve leveraged their fame into global business interests. Michael Jordan, LeBron James, and others have built empires that rely on their status as icons of Black achievement. Their brands are built on the narrative of overcoming racial adversity, “making it out,” and representing a community that’s still fighting for equality. But look closer, and you’ll see how these figures often skim over the messy distinctions between African, Caribbean, and African American identities. The message is unity—one Black experience, one Black market. That unity is great for selling sneakers, jerseys, and music, but it glosses over the fact that not everyone in this big tent has the same story, or the same stake in what “progress” means.

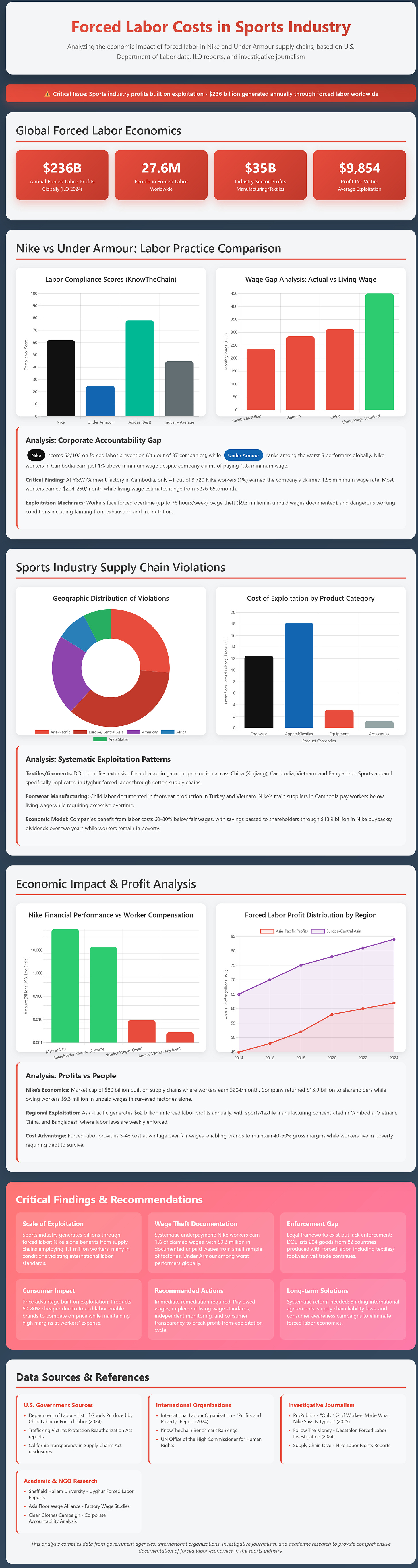

Why does this matter? Because when it comes to labor and exploitation, the lines between race and class get deliberately blurred. Take the NBA’s relationship with Chinese shoe companies—brands like Li-Ning and Anta, which have been linked to forced labor in Xinjiang and elsewhere, NBA players profiting off slave labor, and modern-day slavery in basketball. Black athletes profit from deals with companies accused of using, or being complicit in, modern-day slavery. When pressed, the conversation rarely turns to race; instead, it’s framed as a question of class, of business, of “market realities.” The logic is that since these companies aren’t exploiting Black Americans, but (mostly Asian) factory workers abroad, it’s not quite the same moral issue. It becomes a story about global capitalism, not racial solidarity.

There have been public protests against this selective outrage—like when Enes Kanter called out Nike over China—but most high-profile Black billionaires and athletes have stayed silent. For the American public, especially Black Americans, there’s a strange comfort in this arrangement. Black billionaires and celebrities are proof that “we made it”—that the system can work, that the legacy of slavery is something to be overcome, not something ongoing. But this comfort comes at a price: it means looking away from exploitation when it benefits “us,” or when the victims are “not our people.” The narrative shifts away from race and toward class, but only selectively. There’s outrage when the exploited are Black, and indifference when they’re not.

Meanwhile, multinationals brands—Nike, Under Armour, and others—have been called out repeatedly for labor abuses in their supply chains. Activists have pushed for accountability, but the celebrity partners who could force the issue often stay quiet. The market share and the global “Black” brand are just too big to risk. The result is a kind of selective empathy: the legacy of slavery is invoked when it’s profitable, and ignored when it’s inconvenient.

This isn’t just about hypocrisy. It’s about how power works—how race and class are deployed to protect markets and shape narratives. The conflation of African, Caribbean, and African American identities makes it easier for billionaires and brands to claim a kind of universal Blackness, one that’s both marketable and malleable. But it also makes it easier to sidestep the uncomfortable truth: that slavery, in various forms, is still with us, and that those who profit most are often the most comfortable with looking away, including Black Americans as long as the victims are on the other side of the supply chain.

Real solidarity—across race, nationality, and class—would require a more honest reckoning. It would mean admitting that Black success in America doesn’t erase exploitation elsewhere, and that market share isn’t a replacement for justice. Until then, the conflation will continue, and the profits will keep rolling in.

Rap Culture, Rape Culture, and the Line Between Art and Exploitation

Let’s be honest: a lot of the music that’s shaped the last forty years—especially in rap—hasn’t exactly been kind to women. I’ve listened to plenty of artists who fit this category. The beats are hypnotic, the wordplay is clever, and the hooks stick in your head for days. But none of that makes the sting of reality any softer. The fact that I’ve vibed to these tracks doesn’t make the underlying truths go away.

The conversation about misogyny in rap is as old as the genre itself. From the start, hip-hop was a voice for the voiceless, a way to tell stories ignored by mainstream America. But as it grew, parts of the culture turned women into props or punchlines. It’s impossible to ignore lyrics that glorify conquest, violence, or control over women, or the way these messages get soaked up—then repeated—by the culture at large.

Writers like Joan Morgan and Julie Bindel have spent decades wrestling with these contradictions. Morgan, a self-described “hip-hop feminist,” has argued that loving the music and hating the misogyny isn’t just possible—it’s necessary. You can pump your fist to the beat and still call out the harm in the lyrics. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy to draw the line between art and exploitation.

The Prindle Institute points out that the problem isn’t just what’s said in the music—it's what happens outside of it. Misogyny in rap doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s tied to the larger culture, where Black women in particular face both racism and sexism, and where their pain is often dismissed as “just entertainment.” The LA Times recently highlighted how the #MeToo movement has rippled through hip-hop, especially with allegations against major industry figures. But for every headline, there are countless stories that never make the news.

What’s especially frustrating is the double standard. As The Blackprint notes, male artists are rarely held accountable for lyrics or actions that would end other careers in a heartbeat. Meanwhile, women in hip-hop who speak out—or even just exist—are subjected to scrutiny and criticism most men never face.

Some argue that rap is just reflecting the world as it is. There’s truth to that. The genre has always been raw, unfiltered, and brutally honest about life’s uglier sides. But as Derek Minor points out, that honesty can turn into apathy: “Rap culture does not care about #MeToo,” he says, calling out the industry’s indifference. And as a study in Men and Masculinities found, repeated exposure to these themes can normalize harmful behaviors—not just for listeners, but for the artists themselves.

Of course, not everyone in hip-hop is guilty. There are artists—women and men—who use their platforms to challenge misogyny, tell new stories, and carve out space for something better. As explored in this academic thesis, the genre is evolving, and there are real efforts to shift the narrative. But change is slow, and the old patterns die hard.

I keep coming back to the uncomfortable fact: I’ve listened to and enjoyed music that’s part of the problem. It’s not enough to shrug and say, “Well, that’s just how it is.” Enjoying the art doesn’t erase the exploitation. If anything, it makes confronting it more urgent. The line between art and exploitation isn’t always clear—but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to find it, and push it in the right direction.

The truth is, loving hip-hop means wrestling with its flaws. You can appreciate the brilliance and still demand better. Pretending the problem doesn’t exist—or pretending it doesn’t matter because you like the song—just lets the harm keep repeating. And that’s on all of us, whether we’re making the music or just hitting play.

Legitimizing violence—whether through lyrics, visuals, or the attitudes that get passed around in the culture—doesn’t make for a peaceful or cooperative society. When violence and domination are painted as normal, or even aspirational, it shapes how people treat each other in the real world. The impact stretches far beyond the music, affecting relationships, communities, and the way people imagine their own futures.

When wealth, rap, professional sports, and misogyny converge as aspirational models without structural accountability, they can reinforce cycles of consumerism, gender inequality, and cultural detachment from broader educational or civic engagement—ultimately weakening the social fabric in vulnerable communities.

Yoga, India, Spirituality and Black Celebrity Appropriation

Yoga’s journey from ancient Indian practice to $20 drop-in classes on the West Side of LA is a strange one. What started as a spiritual and philosophical discipline rooted in the Indian subcontinent is now a multi-billion-dollar global industry. The irony is hard to miss: in the West, yoga is both venerated and rebranded, often stripped of its cultural and religious origins in favor of something more marketable. This is especially visible in how Black celebrities and influencers have embraced—and, sometimes, appropriated. Yoga and India have been commodified across religious and ideological lines by reframing ancient spiritual practices into marketable, sanitized products. Each tradition—whether Christian, Islamic, New Age, secular, or Hindu nationalist—has selectively reinterpreted yoga to fit its own moral, political, or consumer frameworks, often erasing its philosophical depth and cultural origins. India itself is marketed as a mystical brand, while its symbols are repurposed for global consumption. But it’s also become associated with male violence and money. To the negation of human rights violations.

India’s own yoga leaders have become global icons. Take Sadhguru, founder of the Isha Foundation. He’s courted celebrities and built an empire that draws everyone from Will Smith to Juhi Chawla to Kangana Ranaut, all eager to be seen as spiritually enlightened through association with his brand. But Sadhguru’s rise has not been without controversy. Allegations of illegal land acquisition, sexual abuse, and run-ins with law enforcement have dogged the Isha Foundation for years. Yet the controversies rarely make a dent in his American fanbase. If anything, the scandals add a hint of exotic danger to the “authentic” guru experience sought after by Westerners, including Black celebrities.

On the other side of the equation are organizations like Black Women's Yoga Collective, which are trying to reclaim yoga as a tool for healing and community among Black women. Their mission isn’t about appropriation, but about survival—using yoga to address generational trauma, health disparities, and the need for safe, affirming spaces. In this context, yoga is less a fashionable accessory and more a lifeline, a way to connect to something deeper while navigating a world that often feels hostile. As it should be.

Appropriation gets even murkier when you look at how yoga, along with other cultural practices, gets filtered through the lens of American race and beauty politics. Just as “yoga bodies” are often depicted as slim, flexible, and white, conversations around beauty and identity can slide from appreciation into appropriation—sometimes with racialized undertones. Practices like "asian fishing," where non-Asian influencers adopt stereotypical Asian features for trend or clout, show how quickly appreciation can turn into something much more exploitative. The politics of caste and colorism echo across continents, shaping both South Asian and Black American experiences.

So where does appropriation come in? When Black celebrities and influencers adopt yoga, sometimes the practice is stripped of its history—a history shaped by colonialism, caste, and the commercialization of Indian spirituality. There’s a risk of erasing the struggles of both Indian and Black communities in favor of shallow “wellness” aesthetics. The challenge is to find a way to honor yoga’s roots while adapting it for survival and resistance, rather than turning it into just another status symbol.

The conversation isn’t just about who practices yoga, but how and why. It’s about the difference between cultural appreciation and appropriation, about who profits, who is seen as legitimate, and who gets left out. In the end, yoga in America is a mirror: what we see reflected says as much about us as it does about the practice itself. Consumerism, faux religion, and misogyny often operate as tools of distraction and control—glossing over systemic caste and racial hierarchies by offering spectacle in place of substance. In both the Dalit experience in India and the Black American experience, these forces can conflate spiritual identity with marketable suffering, reinforcing social exclusion while masking it as cultural empowerment. They also eliminate historical/real progress with regressive attitudes.

Narco Cults and Black Narco Cults: Spirituality in the Drug Trade

The line between faith and criminality gets blurred in the world of narco cults—religious or pseudo-religious groups whose beliefs and imagery are co-opted by traffickers. Most people have heard of Mexican folk saints like Santa Muerte and Jesús Malverde, but the phenomenon runs deeper, especially when you look at the influence of Afro-Caribbean and Black spiritual traditions.

Religions such as Santería and Palo Mayombe, which trace their roots to West African spirituality, have been widely misunderstood and misrepresented. While these faiths are practiced peacefully by millions, drug traffickers sometimes hijack their rituals, symbols, and shrines to lend an aura of mystical protection or power to their operations. As described in Narco-Cults: Understanding the Use of Afro-Caribbean and Mexican Religious Cultures in the Drug Wars, cartels often use these spiritual systems to justify violence, cement loyalty, and intimidate both members and outsiders. Altars, ritual artifacts, and ceremonial practices become signifiers of gang allegiance and sources of psychological reinforcement.

Black Cults & Narco Cults in America

The story doesn’t stop in Latin America. In the United States, Black cult leaders in the mid-20th century—figures like Prophet Jones and Daddy Grace—built powerful, sometimes controversial, religious movements. According to Afropean, these leaders often blended Christian themes with African-derived rituals, creating new hybrid faiths. Though most of these groups were not criminal by nature, some splintered into illicit activities, using spiritual charisma and secrecy as shields for their operations. What’s striking isn’t just the use of religious iconography—it’s how rituals and beliefs can serve as both protection and glue for criminal organizations. Research from the U.S. Department of Justice and academic sources like Springer and Oxford Academic points out that objects such as ngangas (spirit cauldrons) or animal sacrifices are believed to offer protection from law enforcement or enemies. Within the narco world, these practices become a kind of “spiritual operational security”—a way to foster loyalty and trust (or fear) among members. For a deeper look at the social science behind this, see the Journal of Social Sciences. Globally, the tendency to equate African and Black religious practices with criminality continues to cause misunderstanding and stigma. As highlighted in this BBC report, criminal groups sometimes exploit these misconceptions to hide their activities or gain an edge. Narco cults—especially those rooted in Black and Afro-Caribbean spirituality—show how faith can be twisted for criminal ends. But it’s important not to confuse the faiths themselves with these appropriations. Real understanding means separating myth from reality and recognizing the deep cultural nuances at play.

BLM, Financing, and the Palestine Connection

Suffering, Struggle, and the Long Shadow of History: Black Lives Matter, Biblical Legacy, and the Human Cost of Marxism

Behind every headline about Black Lives Matter or Palestine, there’s a human story—often one of pain, resilience, and the desperate hope for dignity. The urge to draw lines—left and right, oppressor and oppressed, “us” and “them”—is as old as politics, but it almost always leaves someone’s real experience out of the picture.

Reading accounts from different corners of the world, it’s hard to ignore how violence lingers. In the U.S., as Du Bois wrote, the legacy of slavery and exclusion still shapes the lives of Black Americans. For Palestinians, as explored in Palestine Studies, the legacy is one of dispossession. The details are different; the ache is familiar. For Jewish people, too, history carries scars—centuries of persecution, exile, and the trauma of the Holocaust continue to echo across generations. Each story is distinct, but the pain of loss and the struggle for dignity are threads that tie these histories together.

Violence—whether by the state, by systems, or simply by history refusing to let go—creates wounds that don’t heal in a generation. Angela Davis, in her interviews, returns again and again to this point: suffering is not just about identity, but about the systems that keep pain alive, long after the first blow has landed.

Class, Labor, and the Universal Struggle

It’s easy to see these struggles as only about race, or only about nationality/religion. But that lets too many people off the hook. Whether you’re a Black worker in Memphis in the 1960s or a Mexican farmer today, you’re caught in systems that value profit and power over people. Class struggle and labor exploitation remain urgent, as much a part of today as yesterday. When you zoom out, the borders blur—pain and resilience start to look achingly similar across the map. Marxist frameworks, while incisive in class analysis, often fail to account for the enduring hierarchies and the transhistorical oppression of diverse peoples—overlooking that slavery, though deeply racialized in modern contexts, has existed across civilizations irrespective of race. Big tent politics often function less as inclusive coalitions and more as strategic psyops—shifting allegiances that obscure the enduring human sins of corruption, greed, and avarice beneath a veneer of unity.

The Dangers of Biblical Framing

Too often, conflict—is recast in biblical terms. This move, whether intentional or not, strips away the messy, modern, human details. Turning today’s suffering into a story about ancient hatreds erases the real people living with the consequences now. It’s easier to talk about prophecy or destiny than about checkpoints, lost homes, or the anxiety of a mother sending her child out the door.

The Common Thread: Human Suffering

The specifics matter, but the feelings do not belong to one group. The sense of being unseen, of being treated as less than, of having your pain become a political talking point—these are universal. The Council of Europe and groups like Common Justice remind us that healing, whether in Baltimore or Bethlehem, requires seeing each other’s humanity first.

In the global theater of human suffering, marxist solidarity has consumed disproportionate moral oxygen—dominating headlines, hashtags, and diplomatic discourse—while countless other nations endure in near silence. This isn't a dismissal of their gravity, but a reckoning with how attention is distributed. Sudan bleeds, Haiti collapses, Yemen starves, and Congo mourns—yet their agony rarely breaches the surface of mainstream empathy. The saturation of focus on a few symbolic struggles risks emotional exhaustion, strategic blindness, and a narrowing of our moral imagination. When suffering becomes a competition for visibility, we lose the capacity to triage compassion, to respond with nuance, and to honor the full spectrum of human pain. Expanding the aperture of attention isn’t just ethical—it’s essential to building a conscience that can breathe.

What Gets Lost

When the conversation is flattened into “left vs. right,” or when ancient scripts are used to justify today’s suffering, the complexity disappears. There are no easy parallels, no neat heroes and villains. There are just people—sometimes part of a minority, always part of the human story—trying to live, to work, to be safe, to matter.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s words at Brandeis still ring out: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” The legacy of violence is long. The struggle is longer. But the possibility of recognizing our shared suffering—and our shared capacity to heal—remains.

Maybe that’s the real connection: between all people who have ever been told their pain is less important than someone else’s story. There’s a through line running beneath all these experiences—a knot of pain, power, and performance. At every turn, you find human suffering at the center: not just as something private and silent, but as a currency that’s traded, branded, and sometimes even sold back to us, wrapped in the language of progress or spirituality or art.

Look at how so many stories get told through a Biblical lens. It’s tempting to frame struggle as fate or divine lesson, but that can make us numb to material realities—class, labor, the actual sweat and hunger and fear that define people’s lives. When you call poverty a cross to bear, you risk justifying it, even glamorizing it, instead of fighting to end it. The same goes for violence: when we talk about “original sin” or “cycles of violence,” it’s easy to forget the legacy of policy and power that keeps certain people vulnerable, and others safe.

Black Lives Matter, the fight for Palestine, the endless question of who gets funded, who gets left behind—all of it comes down to whose suffering is seen, and whose pain is profitable. There’s a strange, ugly symmetry in how movements for justice get commodified, how the pain at the root of them becomes another logo, another hashtag, another influencer’s talking point. Even spirituality isn’t immune. Yoga, once a practice of discipline and humility, gets stripped for parts and sold back as self-care, a lifestyle—sometimes by Black celebrities searching for enlightenment, sometimes by corporations looking for the next trend. You see the same thing in rap: pain and struggle get distilled into lyrics, but the line between art and exploitation blurs. What’s catharsis for some is a business for others. And beneath all of it is rape culture—how violence, especially against women, gets normalized, even celebrated, when it makes for good content or a tougher brand.

When you zoom out, you see a pattern: Blackness, and the suffering tied to it, becomes a brand. Slavery’s legacy morphs into modern feudalism, with class lines drawn sharper than ever. The Curry family turns basketball success into a kind of religous royalty, but even there, you see the comfortable distance of power—the way influence can shelter you, or corrupt you, or both. Sports, religion, art, activism: they all become battlegrounds for influence, for who gets to tell the story and who gets paid for it.

And maybe that’s the core of how we fail our young men. We hand them stories about glory and grit, but we don’t always teach them how the world really works—that suffering isn’t destiny, that art and activism can be co-opted, that money and power rarely trickle down. Too many are left emotionally and financially poorer, navigating a system that only values their pain when it can be packaged, sold, or used as a shield by someone higher up.

This isn’t just about individuals or movements or moments. It’s about the machinery grinding underneath, the way suffering becomes spectacle, and the way distance—between rich and poor, powerful and powerless, those who grieve and those who watch—keeps us from ever really fixing what’s broken.

Conclusion:

There’s no easy way to wrap a bow around all of this. The contradictions at the heart of Black celebrity, activism, and cultural power aren’t just media talking points—they’re the fault lines running through American life. The same hands that lift up slogans for justice can just as easily grab for profit or protection. The same movements that promise liberation can calcify into new hierarchies, swapping out old gatekeepers for new ones. And yet, the real stories—of suffering, solidarity, survival—still matter, even when they’re overshadowed by spectacle.

If there’s a lesson here, maybe it’s that vigilance and honesty matter more than allegiance to any brand, celebrity, or movement. It’s not enough to point out hypocrisy or to tally up who’s winning and who’s left behind. The harder work is to refuse easy narratives, to stay suspicious of power no matter who holds it, and to insist that justice means something deeper than hashtags or headlines. As long as race is currency, weapon, and mask, the job is to keep looking behind it—to demand a reckoning that includes everyone, not just the chosen few.

That kind of reckoning won’t come from celebrity, or branding, or even the loudest voices on social media. It comes from the ground up: from people willing to question, to notice, and—maybe most of all—to care when it’s inconvenient. The only way through the tangle of contradiction and exploitation is to keep asking who benefits, who pays, and how we can build something that’s actually worth believing in.

"This essay presents analysis, opinion, and commentary based on publicly available sources. Where allegations or controversies are discussed, they reflect reported claims rather than established facts unless specifically noted. Readers should consult original sources and form their own conclusions. The views expressed are those of the author and do not constitute legal, financial, or professional advice. All data is publically available"

Designed with Claude & Hyperwrite.